AI Agents Are People (For Now)

AI that substitutes for a human is functionally 'headcount'. AI that optimises an already-automated process is just better software.

When Klarna's AI assistant replaced 700 customer service agents, the company did not install new software. It 'hired' a digital workforce. When Salesforce cut 4,000 support staff and deployed AI to handle a million conversations, it did not automate a process. It substituted one type of worker for another.

This distinction matters. An AI agent that answers customer queries in place of a human who used to answer those queries is not the same as an algorithm that optimises server load. The first displaces a person. The second improves a machine. Yet most organisations classify both as technology costs, governed by IT, invisible to workforce planning.

This is not an issue (yet) but could create even more ambiguity.

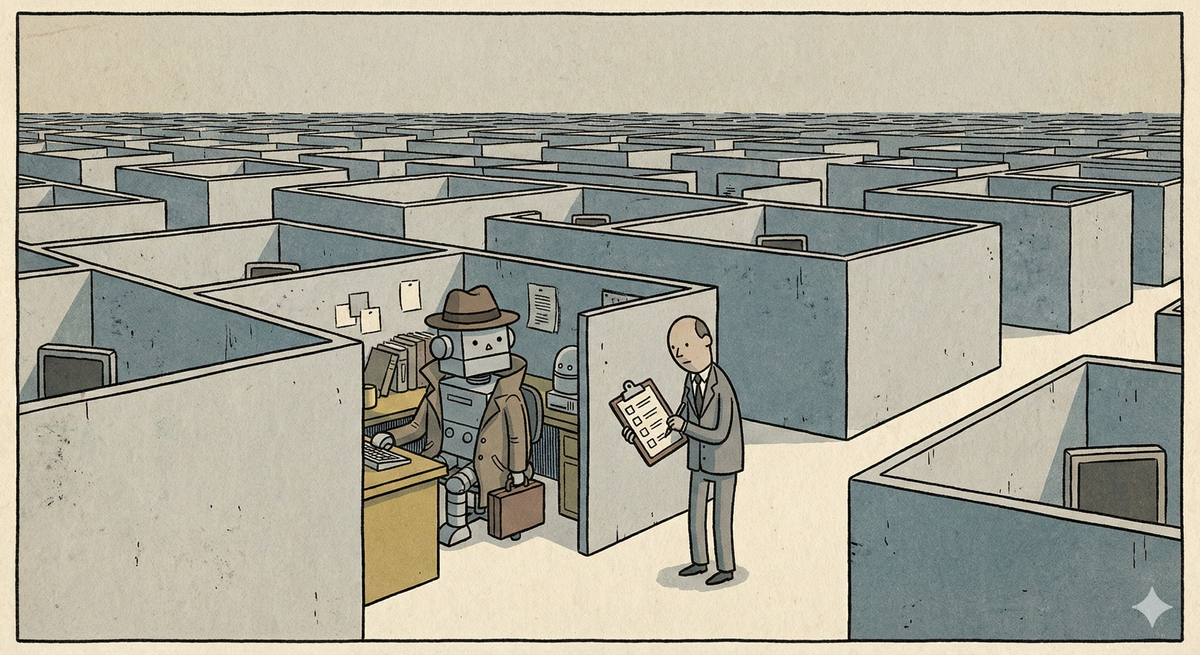

The shadow workforce, version 2.0

Thirty years ago, contract workers began filling roles that permanent employees once held. They sat at the same desks, did the same work, reported to the same managers. But because they arrived through Procurement rather than HR, they existed in a governance vacuum. No one counted them in headcount. No one included them in workforce planning. No one asked whether the organisation's actual labour force matched its org chart.

AI agents are following the same trajectory, only faster. BCG and MIT Sloan report that 76% of executives now view agentic AI as a "co-worker" rather than a tool. McKinsey's Jorge Amar states plainly: "I do think of it as a workforce... we should think of agents as a parallel workforce for all intents and purposes." Some pioneering companies are expressing org charts not just in FTEs but in agents deployed per function.

Yet only 26% of organisations have an AI strategy. Fewer still have formal governance policies for AI agents. The question of who owns them remains contested: IT claims technical deployment, HR claims workforce implications, Procurement claims vendor management, and business units claim operational control. Sound familiar?

The substitution test

Here is a useful distinction that no one has formalised: AI that substitutes for a human is functionally 'headcount'. AI that optimises an already-automated process is just better software.

When an AI sales development representative books meetings that a human SDR used to book, the organisation has not improved a system. It has replaced a worker. The role persists; only the entity filling it has changed. This AI agent should appear somewhere in workforce planning. It should have an owner.

Someone should ask whether it is performing, whether it needs "training" on new data, whether it should be "promoted" to more complex tasks or "fired" for poor results.

When an AI model improves supply chain forecasting that was already algorithmic, no substitution has occurred. This is optimisation, not displacement. Classify it as technology, govern it through IT, and move on.

The trouble is that organisations are not making this distinction. Gartner found that 82% of leaders plan to expand "digital labour" capacity within 12 months, with 33% considering headcount reductions as a result. The agents replacing those humans will be classified as software subscriptions. They will vanish into IT budgets. No one will count them.

A transitional moment

This will not last. Every wave of automation follows the same arc: what begins as a jarring substitution for human labour eventually becomes invisible infrastructure. The first ATMs replaced bank tellers. Now they are simply how cash works. The first automated phone banks replaced receptionists. Now they are simply how calls route.

AI agents will travel this path too. In five years, an AI that handles customer queries will seem no more remarkable than a database that stores customer records. It will be infrastructure, not workforce. The substitution will be forgotten.

But we are not there yet. Today, organisations are actively replacing humans with AI agents and pretending they are merely upgrading software. Klarna cut 40% of its workforce (and is now hiring them back). Salesforce cut thousands. IBM plans to eliminate 30% of back-office roles. These are workforce decisions dressed as technology investments.

The risk is that AI agents slip into the same ungoverned space where contingent workers languished for decades. No ownership. No accountability. No visibility. Maybe a new shadow workforce, growing in the gap between functions while the CPO thinks it belongs to the CIO and the CHRO thinks it belongs to neither.

Workday launched an "Agent System of Record", explicitly designed to manage AI agents alongside human workers. Microsoft's Agent 365 gives each AI its own identity in the corporate directory. These are early attempts to govern what is, for now, a workforce.

The question is whether organisations will learn from the contingent workforce debacle or repeat it. The window for treating AI agents as a governed workforce category is open. It will not stay open long.