The Modern Work Regime

In 1930 an economist with three names (John Maynard Keynes) made a prediction: by the end of the 20th century, technological advancements in countries like the United States and Great Britain would be sufficient to achieve a 15-hour work week.1 Technologically, Keynes was correct; the productive capacity of these nations far exceeded what would be required to meet this goal. Yet, the prophesied utopia never materialized. Instead, technology has been marshaled not to free humanity from labor, but to devise new ways to make everyone work more. To achieve this, a vast number of jobs have been created that are, by the admission of those who perform them, effectively pointless.1

This contradiction lies at the heart of the theory of "bullshit jobs," a concept first articulated by the anthropologist David Graeber in a 2013 essay for Strike! magazine titled "On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs".1 The essay was based on a hunch: that society is riddled with useless occupations that holders are aware are useless, and that this situation creates a profound, yet unspoken, "psychic wound".1 The response was immediate and explosive. The essay went viral, was translated into over a dozen languages, and prompted a flood of confessions from white-collar professionals who recognized their own working lives in Graeber's description.1 This initial public reaction served as a powerful, if anecdotal, validation of the theory.

The phenomenon was soon confirmed by statistical research. In 2015, the polling agency YouGov, using language taken directly from the essay, surveyed British workers. The results were astonishing: 37% of respondents stated they did not believe their job made a "meaningful contribution to the world," while 50% believed it did, and 13% were uncertain. A subsequent poll in the Netherlands produced even higher numbers, with 40% of Dutch workers reporting that their jobs had no good reason to exist.1 These figures, nearly double what Graeber himself had anticipated, confirmed that pointless employment is not a marginal issue but a core feature of modern economic life.1

Defining the "Bullshit Job": Subjectivity as a Diagnostic Tool

To analyze this phenomenon, a clear definition is required. After considering and refining several possibilities, Graeber arrived at a final working definition: a bullshit job is "a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case".1

This definition hinges on a critical methodological choice: the elevation of the subjective element. While the social value of any given job is notoriously difficult to measure objectively, Graeber contends that the perspective of the worker is the most reliable diagnostic tool available. If the person performing a job day in and day out is convinced that it is pointless, they are almost certainly correct. This is because, unlike an outside observer, the worker has direct, firsthand knowledge of the tasks being performed, their purpose within the organization, and their ultimate effect on the world. While managers might insist that underlings cannot see the "big picture," it is far more common for those at the bottom of a hierarchy to have a clearer view of the operational realities than those at the top, from whom information is often concealed.1

It is crucial to distinguish "bullshit jobs" from what are commonly referred to as "shit jobs." The two are frequently confused but are, in fact, almost polar opposites. Shit jobs are typically forms of labor that are necessary and clearly beneficial to society—such as cleaning, waste collection, or basic service provision—but which are characterized by low pay, poor working conditions, and a lack of respect. In contrast, bullshit jobs are often well-compensated, offer comfortable working environments, and are surrounded by prestige and honor. The oppression of a shit job lies in its exploitation and indignity; the oppression of a bullshit job lies in its spiritual violence and profound pointlessness.1

The existence of bullshit jobs presents a fundamental paradox for conventional economic thought. Neoliberal ideology, which has dominated public policy since the 1980s, is founded on the principle of market efficiency. In a truly competitive market, profit-seeking firms should be the last entities to pay people to do nothing. The creation of pointless jobs for political reasons, such as the full-employment policies of the Soviet Union, is precisely the kind of inefficiency that market competition is supposed to eliminate.1 Yet, the data suggests that while productive, blue-collar jobs have been relentlessly squeezed and automated, the number of salaried, white-collar administrative roles has expanded dramatically.1 This leads to an inescapable conclusion that drives the book's entire inquiry: if the proliferation of pointless work cannot be explained by economic logic, its causes must be sought in the moral and political spheres. The system is not behaving irrationally; it is simply operating according to a different, unstated logic rooted in the maintenance of social control and the preservation of power structures.1

The Five Categories of Bullshit Jobs

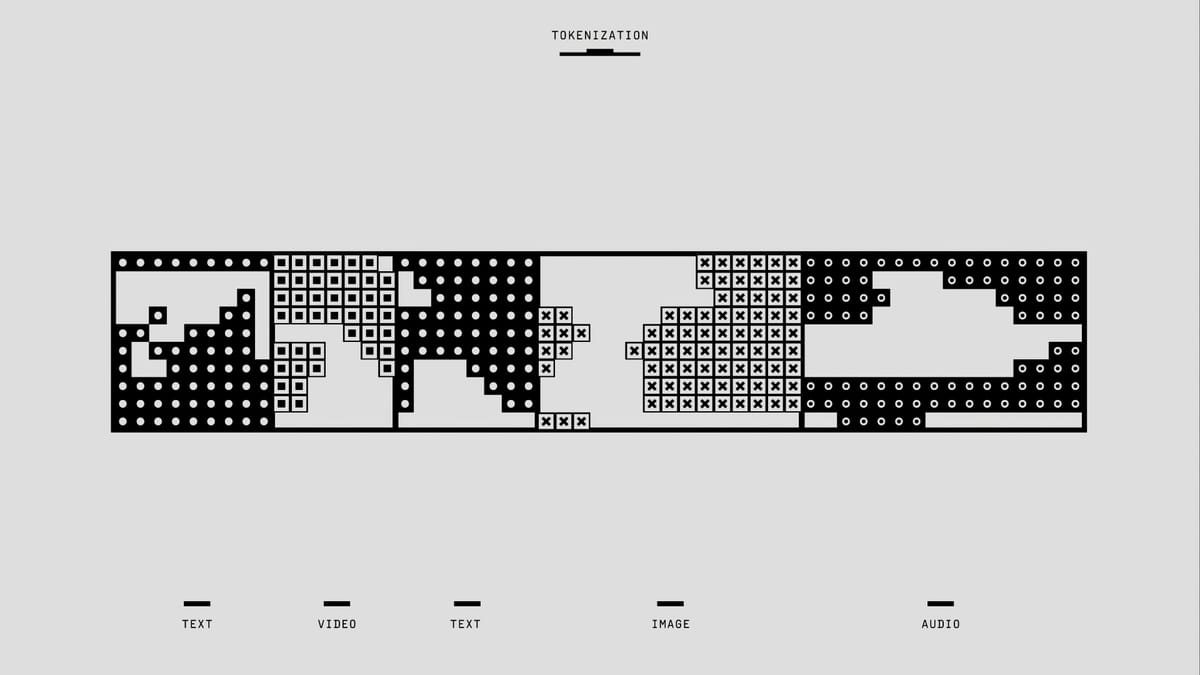

Based on an analysis of over 250 firsthand testimonies from individuals who believe they hold or have held a bullshit job, Graeber developed a typology of five primary categories of pointless work. These categories are not merely descriptive; they reveal the internal logic of a system where hierarchy, competition, and performativity have superseded productive efficiency as the primary organizational principles.1

1. Flunkies

Flunky jobs are those that exist primarily to make someone else look or feel important. They are the modern equivalent of feudal retainers, whose presence serves to signify the status and prestige of a superior. The very uselessness of the flunky is a testament to the grandee's power. This category includes roles such as doormen in luxury buildings who perform the same function as an electronic intercom, or receptionists in offices that receive almost no visitors or phone calls.1 Their presence is required not for any functional reason, but as a "Badge of Seriousness" or a "Badge of Importance." A company without a receptionist, for instance, might not be taken seriously, as it would be seen as violating a basic convention of corporate legitimacy.1 At a more granular level, a manager's importance is often measured by the number of subordinates they command, creating a powerful incentive to hire staff regardless of whether there is any actual work for them to do. This can lead to perverse dynamics where assistants are hired solely to make a superior appear too busy to handle their own calls, creating a status symbol within a competitive office environment.1

2. Goons

The "goon" category comprises jobs that have an aggressive or manipulative element and exist only because other organizations employ people in similar roles. National armies are a classic example: countries need armies primarily because other countries have them. The same logic applies to a host of corporate professions, such as lobbyists, public relations specialists, telemarketers, and corporate lawyers.1 Many who hold these jobs are aware of their negative social impact. A corporate tax litigator confessed, "I contribute nothing to this world and am utterly miserable all of the time".1 The defining characteristic of goon jobs is not just their lack of positive social value, but their inherently manipulative and aggressive nature. This includes the visual effects artist paid a six-figure salary to digitally alter images of women in advertisements, creating feelings of inadequacy to sell beauty products, or the call center employee whose job is to trick people into buying services they do not need.1

3. Duct Tapers

Duct-taper jobs exist solely to solve a problem that ought not to exist. These employees are hired to patch over a fundamental flaw in an organization that, for various reasons, is not being fixed.1 The term is borrowed from the software industry, where coders are often paid to apply "duct tape" to make poorly designed core technologies work together. This category includes underlings whose entire job is to undo the damage done by incompetent superiors, such as a proofreader hired to correct the incoherent reports of a statistically illiterate star researcher.1 It also encompasses a wide range of roles created by systemic glitches that are never addressed, such as the employee whose full-time job is to manually copy and paste information from one software program to another because a previously automated system was nullified by a managerial dispute.1 The moral agony of the duct taper lies in being forced to care about a problem precisely because their superiors cannot be bothered to solve it properly. A paradigmatic example is the university employee whose entire role is to apologize for the fact that a carpenter never arrives to fix a broken shelf, when the university could simply hire another carpenter and eliminate the need for the apologizer.1

4. Box Tickers

Box-ticking jobs exist to allow an organization to claim it is doing something that, in fact, it is not doing. This often involves the creation of paperwork, reports, surveys, or meetings that serve no purpose other than to be produced, creating a performative illusion of activity.1 The care home leisure coordinator whose primary duty was to fill out forms detailing residents' recreational preferences, forms that were then filed away and never read, is a classic example. The most miserable aspect of such jobs is the awareness that the box-ticking exercise not only fails to achieve its ostensible purpose but actively undermines it by diverting time and resources away from it.1 This dynamic is rampant in both government and the corporate sector. It includes the consultant paid £12,000 to write a two-page report for a pharmaceutical company's strategy meeting, a report that was ultimately not used because the meeting ran out of time.1 It also encompasses entire corporate sub-industries, such as in-house magazines or television channels, that exist almost solely to allow executives to see favorable stories about themselves, produced by staff who are fully aware that their work is bullshit.1

5. Taskmasters

Taskmasters fall into two subtypes. The first are those whose role is simply to assign work to others who are perfectly capable of managing themselves; they are unnecessary superiors. The second, and more pernicious, type consists of "bullshit generators": managers whose primary role is to create more bullshit tasks for others to do, supervise bullshit work, or even invent entirely new bullshit jobs.1 A middle manager who admits that his ten subordinates could do their work without his oversight is a type-one taskmaster.1 A more complex example is the non-executive university Dean who, given a staff and a budget but no real power, spends her time "making up work for myself and for other people" by creating strategic vision documents she knows will be ignored.1 Taskmasters are often responsible for "bullshit proliferation," creating a "confetti of paperwork" related to audits, reviews, and performance targets that cascades down the hierarchy, forcing their staff to assist in the generation of more bullshit.1

These five categories are not merely a random collection of pointless roles; they form a coherent model of a dysfunctional and self-perpetuating system. The typology reveals the internal logic of modern corporate bureaucracy. Flunkies and Taskmasters represent the vertical axis of hierarchy, embodying the need for superiors and subordinates regardless of actual function. Goons represent the external, competitive dynamic between organizations that are structured in a similarly irrational way. Duct Tapers and Box Tickers, in turn, represent the internal, systemic inefficiency and performativity that characterize these organizations. Each type of bullshit job can create the conditions for the others to exist: a Taskmaster hires a Flunky to enhance his prestige, then creates box-ticking exercises for his other subordinates to perform, while a Duct Taper is brought in to clean up the resulting messes. The entire organization then hires Goons to compete with rival firms that are engaged in the very same pointless activities. This reveals that the proliferation of bullshit jobs is not an accident, but the logical outcome of a system organized around principles other than utility or efficiency.

| Job Type | Core Function | Illustrative Example from Text |

| Flunky | To make a superior look or feel important. | Doormen, unnecessary receptionists, personal assistants hired as status symbols. |

| Goon | To act aggressively or deceptively on behalf of an employer. | Corporate lawyers, PR specialists, telemarketers, lobbyists. |

| Duct Taper | To solve a problem that should not exist. | Programmers fixing shoddy code, staff who handle complaints caused by incompetent superiors. |

| Box Ticker | To allow an organization to claim it is doing something it is not. | Survey creators whose data is never used, in-house magazine writers, compliance officers. |

| Taskmaster | To supervise people who do not need it, or to create more bullshit work for others. | Middle managers who assign tasks to self-sufficient teams, executives who invent pointless strategic initiatives. |

The Spiritual Violence of the Modern Workplace

The Paradox of Unhappiness: Why is Being Paid to Do Nothing Miserable?

The central psychological puzzle presented by the phenomenon of bullshit jobs is why being paid—often handsomely—to do nothing is a source of profound misery. This reality directly challenges the foundational assumption of classical economics: that human beings are simple calculators of advantage who seek to acquire the most benefit for the least expenditure of effort.1 If this were true, those in bullshit jobs should consider themselves uniquely fortunate. Yet, the overwhelming majority of testimonies reveal feelings of depression, anxiety, worthlessness, and confusion.1

The case of Eric, a recent history graduate from a working-class background, serves as a paradigmatic example. Hired as an "Interface Administrator" for a design firm, he discovered his role was a confluence of duct-taping and box-ticking, created to manage a software system that no one wanted to use and that was intended to solve a communication problem between partners who refused to cooperate. He was hired precisely for his lack of IT skills, ensuring the project would fail. Given a high salary, minimal supervision, and almost no actual work, Eric descended into a spiral of rebellion and self-destruction, attempting to get himself fired by showing up drunk, taking phony business trips, and abandoning all pretense of work. The company responded by repeatedly offering him raises. The situation ultimately led to a mental breakdown, driven by the "profoundly upsetting" realization of living in "a state of utter purposelessness".1

The explanation for this deep-seated unhappiness can be found in fundamental human psychology. In 1901, the German psychologist Karl Groos identified what he called "the pleasure at being the cause"—the profound joy infants experience when they first realize they can cause predictable effects in the world. This experience, he argued, is the very foundation of the human sense of self; we come to understand ourselves as discrete beings by recognizing our own agency.1 Conversely, experiments have shown that when this ability to have an effect is denied, the result is first rage, and then a catatonic withdrawal. This "trauma of failed influence" is a direct assault on the psyche.1

Bullshit jobs can be understood as institutionalized versions of this trauma. They are a form of "spiritual violence" because they attack the very core of what it means to be a human being: the need to see one's actions have a meaningful impact on the world. To be employed in a role where one must pretend to be useful while being keenly aware that one is not, is to have one's sense of self constantly undermined. A human being who is unable to make a meaningful impact on the world, in a very real sense, ceases to exist.1

The Agony of Pretense and Scriptlessness

A key source of this spiritual violence is the element of forced pretense. The employee is not merely idle; they are typically obliged to act as though they are engaged in purposeful activity. This creates a pervasive sense of falseness and alienation. The situation is compounded by a deep ambiguity, a condition that psychologists have termed "scriptlessness".1 In most bullshit jobs, the rules of the charade are unspoken. The employee does not know how much they are expected to pretend, what forms of non-work activity are permissible, or what the consequences of being "found out" might be. This forces them into a constant state of low-grade anxiety and guesswork.1

Supervisory attitudes exist on a spectrum. At one end are managers who sadistically enforce make-work, such as the supervisor who ordered an employee to sort thousands of paper clips by color, only to use them interchangeably afterward.1 At the other end are those who tacitly acknowledge the situation and allow their underlings to "pursue their own projects," though the parameters of this freedom are never explicitly defined and must be carefully negotiated through coded language and indirect signals.1 The vast majority of situations fall into a murky middle ground, where employees must maintain a constant performance of busyness, leading to elaborate strategies like using text-only web browsers that make internet surfing look like complex coding.1

This agony is intensified by the feeling of not being entitled to one's own misery. Society, and often friends and family, tells the worker in a comfortable, well-paid, but pointless job that they should be grateful. This invalidation of their suffering leads to a profound sense of guilt and shame. They feel they have no right to complain, which only deepens their depression and isolation.1 This is particularly acute for younger generations, who are often lectured about their "entitlement" while facing economic prospects worse than their parents', making it almost impossible for them to voice complaints about the meaninglessness of the employment they are told they are lucky to have.1

Guerrilla Purpose: Resistance and Coping Mechanisms

In the face of this spiritual assault, workers are not entirely passive. Many engage in what can be termed "spiritual warfare," developing coping mechanisms and forms of resistance to preserve their sanity and carve out a sense of purpose.1 This "guerrilla purpose" takes many forms. Some engage in covert creative projects, using the furtive moments of downtime to write plays, compose music, or contribute to Wikipedia.1 Others find purpose in political organizing, using their access to office resources and their ample free time to plan actions or unionize their workplaces.1 These acts of creative and political self-assertion serve as a direct antidote to the pointlessness of their official duties.

The very structure of bullshit jobs, however, often limits the scope of this resistance. The psychological toll of anxiety, boredom, and self-doubt is profoundly depleting. It drains workers of the mental and emotional energy required for sustained, ambitious projects. Furthermore, the fragmented and surveilled nature of office time—scattered, furtive shards of freedom—lends itself more to passive consumption of digital media like memes and YouTube videos than to active, collaborative creation, such as forming a rock band or organizing a political movement, which were more common forms of cultural resistance in the era of the mid-20th-century welfare state.1 The spiritual violence of bullshit jobs is not merely a personal tragedy; it functions as a powerful mechanism of social control. By keeping the professional-managerial classes occupied, miserable, and focused inward on their own ambiguous suffering, the system effectively depoliticizes them. It saps them of the energy, confidence, and collective spirit that would be required to challenge the very structures that create their misery, thereby ensuring the stability of the political and economic status quo.1

The Engine of Proliferation: Managerial Feudalism and Financialization

The structural proliferation of bullshit jobs in the late 20th and early 21st centuries is driven by a fundamental transformation in the nature of capitalism itself. The economy has increasingly shifted from a model based on the production and sale of goods to one centered on the extraction and distribution of wealth. Graeber terms this new system "managerial feudalism".1

The Rise of Managerial Feudalism

In classical feudalism, lords extracted a share of the product from peasants and artisans and then distributed this loot among their own hierarchy of retainers, vassals, and staff. The logic was political, not economic; efficiency was not the primary concern. Graeber argues that modern corporate capitalism has come to resemble this structure. Power and prestige within large organizations are no longer primarily tied to productive output but to the size of one's administrative empire. Consequently, managers have a powerful incentive to hire and retain subordinates not for their functional utility but as status symbols, much like feudal lords surrounded themselves with an entourage of flunkies.1 This dynamic explains why, even in the face of automation that could eliminate roles, managers will resist downsizing because it would diminish their own power and prestige within the corporate hierarchy.1

The Infection of Other Sectors

This logic of "managerial feudalism" has spread from the financial sector to infect almost every other area of the economy. The "creative industries," such as film and television, have seen an "endless multiplication of intermediary executive ranks".1 Where once a relatively simple relationship existed between writers, directors, and producers, there is now a labyrinthine hierarchy of executives with titles like "Executive Creative Vice President." These executives justify their existence by interfering in the creative process, demanding endless revisions, pitch documents, and meetings. The result is a system where a vast amount of creative energy is expended on developing projects that are never made, as executives are incentivized to keep ideas in circulation rather than take the risk of approving them.1

The most powerful empirical evidence for this thesis comes from the world of university administration. As the following table illustrates, the growth in administrative layers in US universities has been exponential, far outpacing any growth in the number of students or faculty who constitute the core educational mission of the institution.

This administrative bloat is not a response to increased government regulation; in fact, the rate of administrative growth has been more than twice as high in private universities as in public ones.1 It is a clear example of a self-replicating managerialism, a system where administrators hire more administrators, who in turn require armies of administrative staff, all operating independently of any functional necessity. This is managerial feudalism in its purest form: a system dedicated to its own expansion and the distribution of resources within its own ranks, detached from the productive or social purpose of the organization it inhabits.