Consutling is just a name of a supply chain, it is not even a business verb.

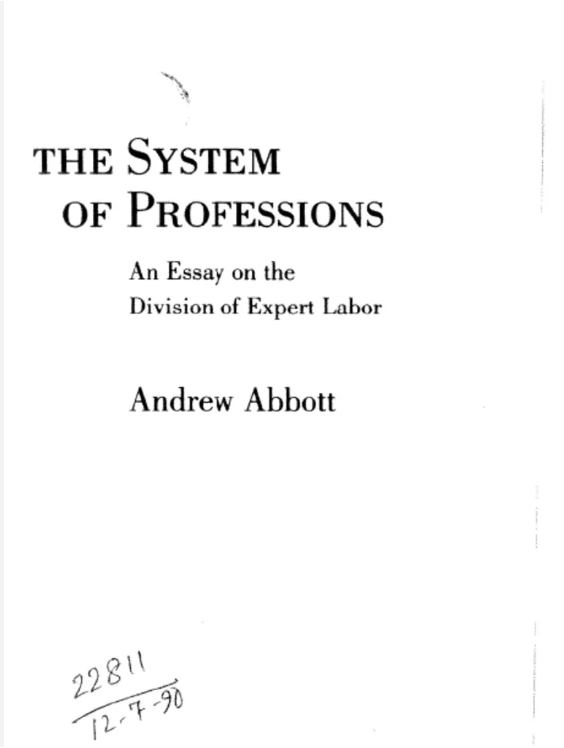

There are certain books that find you at the right time. They don’t just give you answers; they give you better questions. For me, that book was The System of Professions by Andrew Abbott, a sociologist at the University of Chicago. It landed in my hands at the exact moment my team and I were wrestling with a fundamental problem about the nature of work.

After reading it, I sent Andrew a "Hail Mary" email. I never expected a reply.

The Problem That Led Me to the Book

Our startup, Deployed, was born from a simple observation: organizations are often terrible at defining the complex work they need done. They know they have a problem, but articulating it in a way that allows them to find the right expert is a huge challenge. We built a tool to help them do just that—a Q&A platform to systematically define a scope of work and connect with the right consultants or teams.

As we gathered data, our clients started asking a bigger question: "Can't you use this data to help us solve our own problems before we even hire a consultant?"

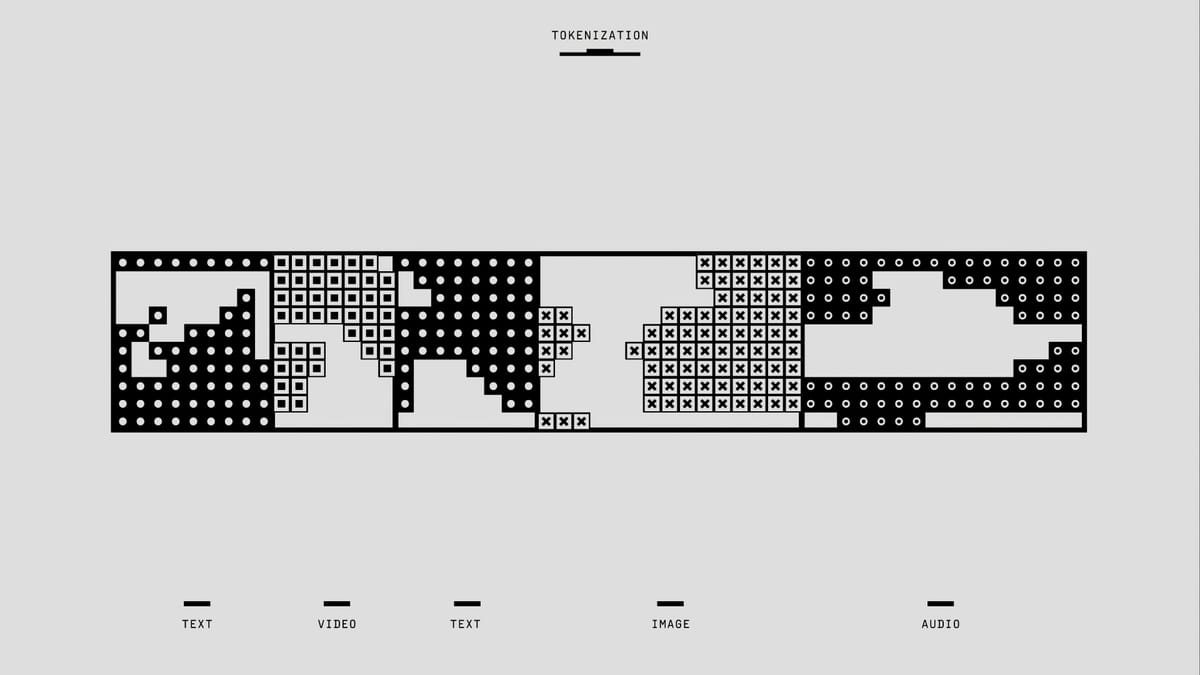

This was a fascinating, and daunting, proposition. We were seeing patterns everywhere. So many high-level consulting projects boiled down to repeatable tasks: project management, business analysis, financial modeling, "producing a report." At the same time, we saw the rise of the "professional gig economy," as it was at the time.

This led to our core dilemma, the one I posed to Professor Abbott: Is the future of consulting firms just to act as clearinghouses for subject matter experts? And more importantly, is a service like ours, which tries to self-diagnose and define work, a step too far?

I summarized this in my email, hit send, and figured that was that.

The Reply: A Dose of Reality

A few days later, an email landed in my inbox. His opening line: "What a fascinating thought – that people would read this book and wonder about its implications for the present. Astounding."

He then proceeded to dismantle my assumptions with surgical precision.

Conclusion 1: Management Consulting Isn't a "Real" Profession

My first mistake was lumping Management Consulting (MC) in with traditional professions like medicine or law. Abbott's book defines a profession by its ability to claim and defend jurisdiction over a specific body of knowledge. He argued that Management Conslulting fails this test.

In his view, consutling is a temporary stop for smart young people on their way to something else. They have a generic grasp of analytical tools (statistics, org theory), but this knowledge isn't unique or monopolizable.

He drove the point home with a sharp anecdote: "A bunch of McKinsey consultants came to this university to consult on some stuff in the 1990s, and they were obviously, plainly incompetent at the techniques they were using – the kind of stuff we would give people B- for in a grad course."

Ouch. His point is that the knowledge base is too slippery and too widely available to be the foundation of a true profession in the historical sense.

Conclusion 2: The "Dance" Is About Politics, Not Truth

So if consulting isn't about expert knowledge, what is it about? This was Prof Abbott's insight. He argued that the "dance" I asked about was indeed the most important part, but not for the reasons I thought.

The purpose of most management consultants, he stated, is "to come and figure out what whoever has hired them wants said, and to then get a bunch of young gophers to produce something that makes that appear to be scientific truth."

The real skill happens in the subtle negotiation between the senior consultant and the client to figure out the desired outcome. The report, the data, and the PowerPoint slides are often just artifacts to justify a decision that has already been made.

This means you can't professionalize the core of that job, because its true purpose is to navigate the client's internal politics. Of course, he noted there are brilliant exceptions—he mentioned a close friend at Bain with a PhD in Anthropology who is a "fabulous social scientist." But they are the exception, not the rule.

Conclusion 3: AI is Just "Superior Flim Flam"

What about AI and machine learning? Surely they can cut through the politics and find objective answers?

Abbott was thoroughly unimpressed. "It goes without saying that the only utility of AI and ML is as a superior kind of flim flam," he wrote.

Because AI is even more of a "black box" than statistics, it has even greater power to legitimize. It carries the veneer of irrefutable science, making it the ultimate tool for dressing up a political decision in the language of objective truth.

The Ultimate Challenge: You Can't Measure What Matters

His final point was directed squarely at Deployed. He recognized that our tool was designed to survey and categorize the tasks that make up "work." But he warned me that we were measuring the wrong thing.

The skills we were identifying—business analysis, data reduction—are commodities. The software that executes them is a commodity. The real value, he argued, isn't in the task itself, but in the wisdom of its application.

"It is impossible to commodify the use of these tools in genuinely intelligent ways," he explained. For that, you need deep training, like a PhD, that teaches you how to think. The friend he mentioned at Bain isn't valuable because he can run a regression; he's valuable because his anthropology background gives him a "genuinely creative manner" for thinking about problems.

My Takeaway: A Better Problem to Solve

Professor Abbott's email was clarifying. And has led me to develop a Business Verb index that we use today in Deployed - not the type of channel delivering the work, but the work that is actually being done.

He gave us a much sharper, more honest framework for what we are doing. What we can do with AI tools is strip away the noise. We can help organizations differentiate between the two types of work Abbott described: the genuine need for "real help" versus the political need for "legitimation." By forcing clarity on the problem statement, we can make it harder for "flim flam" to thrive.

His email affirmed that the future isn't about replacing consultants with AI. It's about creating a more transparent market where the right problems find the right minds. We aren't trying to measure creativity; we're trying to clear the path for it. And for that insight, I am incredibly grateful for a cold email sent to a professor I admire. He didn’t just answer my question; he completely changed it.