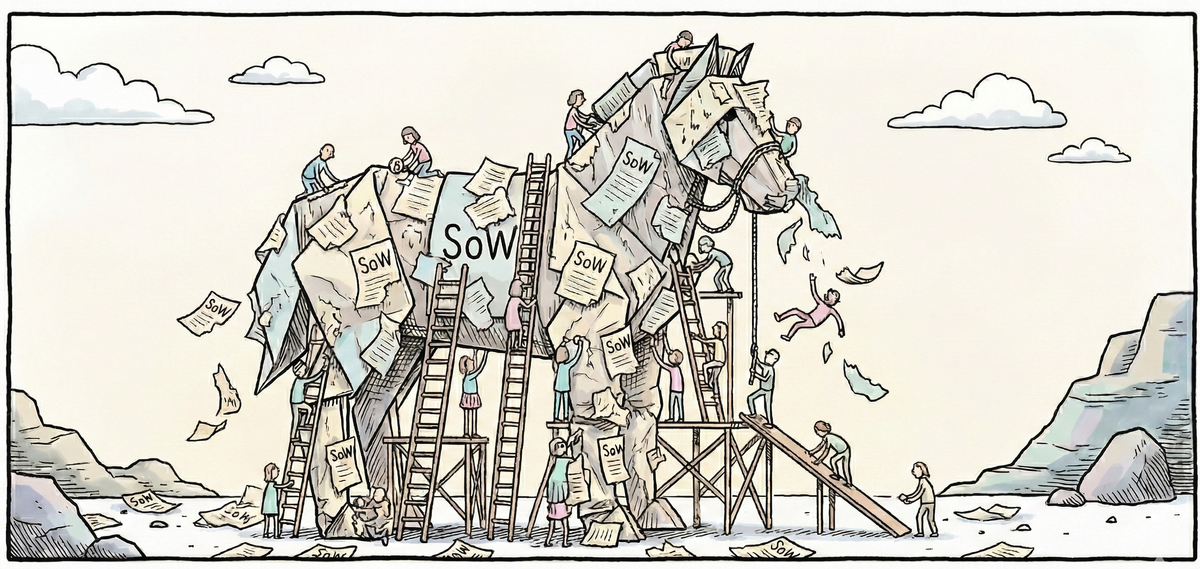

SoW Is Not a Strategy, for goodness sake.

Nobody buys a statement of work, or would think to buy a purchase order, or hire a work order or a permanent contract. They buy services. They hire people. The statement of work is the vehicle through which that purchase is documented.

Everyone knows this is one of Jamie's personal pet peeves. Across enterprise Procurement and HR functions, professionals routinely describe their work as "SoW management" or ask whether a requirement should "go SoW." The language has become so embedded that practitioners have stopped noticing its absurdity. It is akin to a car dealership describing itself as being in the "purchase agreement business."

This instantly shapes how organisations structure governance, measure performance, and allocate resources. And it is costs Enterprises money, and it costs MSPs and BPO's significant revenue opportunities.

The vehicle and the destination

A statement of work is a contract type. It specifies scope, deliverables, acceptance criteria, and payment terms. It is one of several mechanisms through which an organisation can acquire services, sitting alongside time-and-materials agreements, managed service contracts, and outcome-based arrangements.

The services themselves are the point. The contract is the paperwork.

Procurement and HR teams persistently conflate the two. MSPs and CWP leaders are frankly, the worst on this. When a hiring manager submits a request, the intake question is often framed as "Is this a contractor or a SoW?" rather than "What capability do we need and how should we source it?" The former treats contract type as a primary classification; the latter treats it as a downstream decision that follows from understanding the work.

This inversion has consequences. Requestors are forced to navigate procurement taxonomy before they have articulated their actual need. Governance frameworks are built around contract vehicles rather than risk profiles or spend categories. Also you can 'buy' a persons's time with no controls in a SoW, but if framed as buying a service, then requestors can't possibly shoe horn in labour into a service framework; they can into a sh*tty SoW template.

How the default crept in

The confusion emerged from reasonable origins. Two decades ago, managed service providers began extending their contingent workforce programmes into adjacent territory. Having perfected the management of temporary staffing, they encountered project-based work that did not fit the requisition-and-placement model.

These engagements were typically documented through statements of work. The contract type became shorthand for the category. "SoW" distinguished project-based services from staff augmentation in a way that was administratively convenient if conceptually imprecise.

The problem is that administrative convenience calcified into strategic framing. What began as a label for a contract type became, in industry parlance, an entire market segment. Providers now speak of "SoW spend" as though it were a coherent category rather than an artefact of how paperwork happens to be structured.

Meanwhile, the actual services procurement market, worth roughly a thousand times more than the managed "SoW" segment, operates with entirely different vocabulary. Chief Procurement Officers discuss professional services, consulting engagements, outsourced functions, and managed outcomes. They do not describe their strategy as "buying SoWs."

The practical cost

Three specific problems follow from treating a contract vehicle as a supply strategy.

First, intake failures. When requestors are asked whether they need "a SoW," many have no idea what the question means. They know they need a team to build something, or expertise to solve a problem, or capacity to deliver a project. The contract structure is not their concern. Forcing them to navigate procurement jargon before articulating their need creates friction that drives spend outside managed channels entirely.

Second, governance gaps. Organisations that frame their programmes around "SoW management" tend to govern the contract rather than the outcome. They track whether documents were completed correctly, whether approvals were obtained, whether templates were followed. They are less likely to track whether the services delivered value, whether the provider performed, whether the engagement achieved its purpose.

Third, strategic myopia. Defining a market by its contract vehicle obscures the capabilities that actually matter. The skills required to manage services procurement effectively, including scope definition, provider assessment, performance management, and outcome measurement, are valuable regardless of how the paperwork is structured. Framing the work as "SoW management" diminishes it.

Saying what you mean

The correction is straightforward: describe the thing being bought, not the paper it is bought with.

Requestors do not purchase statements of work. They purchase services, outcomes, expertise, and capacity. The statement of work documents that purchase. It specifies what was agreed. It provides legal recourse if commitments are not met. It is important, but it is not the product.

Procurement and HR functions that internalise this distinction will find their conversations with the business become easier. A hiring manager who is asked "What services do you need?" can answer meaningfully. A hiring manager asked "Do you need a SoW?" cannot.

The shift also clarifies what good looks like. Managing services well means ensuring the organisation receives value from its external engagements. Managing statements of work well means ensuring the paperwork is in order. These are not the same thing, and only one of them matters strategically.

The thousand-times market

The services procurement market dwarfs the segment that managed service providers have claimed as "SoW." According to industry analysis, the gap is roughly a thousand-fold.

This disparity should prompt reflection. If the capabilities required to manage services effectively are genuinely valuable, and they are, then the market opportunity extends far beyond the narrow band of tail spend that happens to be documented in a particular contract format.

Capturing that opportunity requires abandoning the vocabulary that confines it. Organisations do not need better SoW management. They need better services procurement: clearer scope definition, more rigorous provider assessment, more disciplined performance management, more honest outcome measurement.

The statement of work will remain part of that process. It is a useful contract vehicle for project-based engagements with defined deliverables. But it is a vehicle, not a destination.

Treating it otherwise is how an industry talks itself into irrelevance.